I’ve been playing with and exploring Event Sourcing for a while now, but only recently realised that part of my thinking might have been muddled by unexamined assumptions about what commands are and what they do in the context of Event Sourcing.

These assumptions started showing their limits after I started building something real based on my (possibly mis-interpreted) understanding of the Decide, Evolve, React pattern.

I’m putting this in writing mainly to track my own learning and to share it with others who might be in the same boat.

The assumption: commands are about “doing” things

Coming from CRUD and OO, my gut understanding of Commands and their handlers in ES/CQRS is that they do things. In my previous post about the command layer I wrote that a command’s role is to:

Inspect the current state, along with whatever input your command expects, run any validations needed, fetch any extra data needed to fulfill the command, and decide if any new events need to be issued.

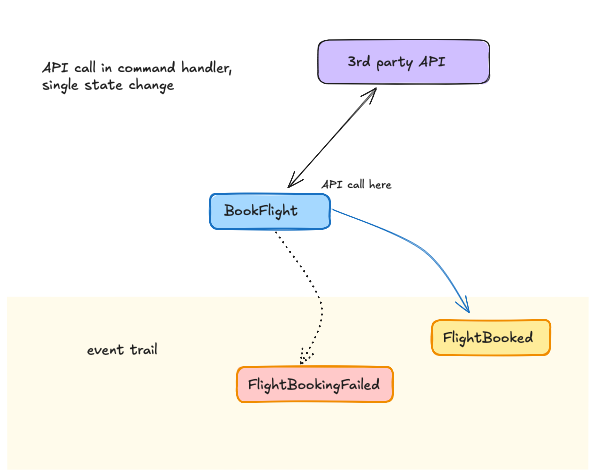

So, commands are operations or self-contained capabilities in a system. They validate their inputs and guard business invariants, sure, but they can also run any side-effects to fulfill the intent of the command. Fetch product data from a catalog API, send a payment request to a payment gateway, or a flight-booking service, etc.

In this view, commands do indeed change the state of the system in the form of published events, but the events are there to track the outcome of the command’s main purpose, which is actually doing something and probably interacting with the outside world.

In my defense, a lot of discussions and examples around ES/CQRS seem to reinforce this view. Commands are often described as operation-oriented “imperatives” that imply side-effects, such as “Book Flight”, “Make Payment”, “Send Email”, etc.

Side-effects need proper state tracking

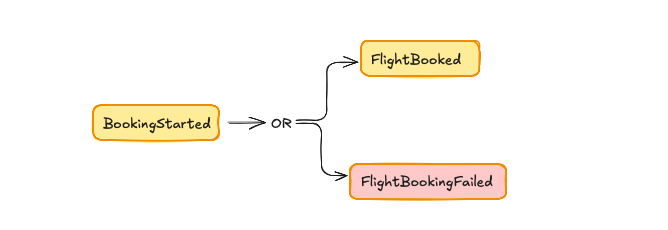

The example in the diagram above is obviously flawed, though. In most such cases you want your system to track the state of the out-going request. The call to the 3rd-party system could fail, timeout, or just take a long time. You could also want to schedule it for later, perform retries, cancellation or block other workers from picking up the same task, etc. I have often achieved this by modeling the operation as a multi-step workflow where I keep track of intermediate states before completion.

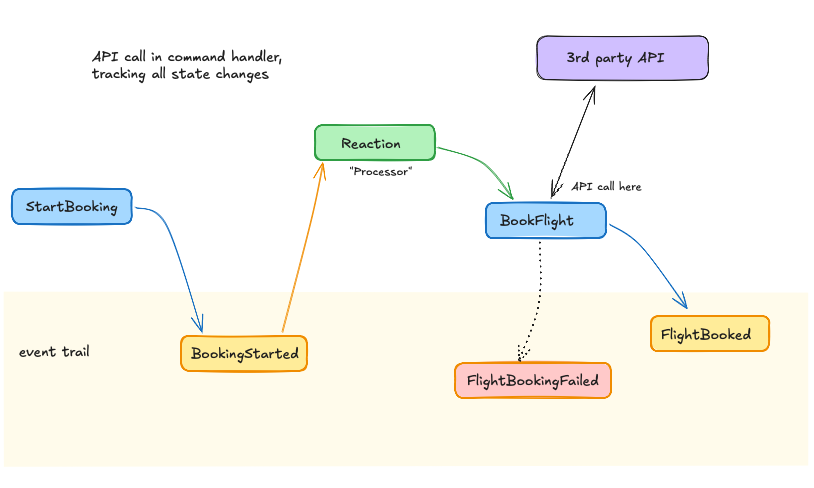

This is where the “react” in Decide, Evolve, React came in for me. Its job was as a fairly dumb trigger to link a command’s resulting events on to the next command in a workflow.

The React step was the glue that holds the workflow together, but Decide (the command handler) was the one that did the actual work, including running any side-effects.

Technically, this works. If you consider Event Sourcing to be all about tracking state changes via events, then all that matters is that after the command is done, the resulting events are stored and can be replayed to reconstruct the state of the system. At a high level you can picture more complex workflows built this way, and they seem almost self-evidently simple.

Deterministic command handlers?

Many articles and discussions out there argued that command handlers should be “pure” and deterministic (they take all state they need as previous events + input, and push all side-effects to infrastructure layers), but most seemed to focus on how this simplifies testing and/or performance instead of any fundamental architectural reason (that I could see).

Now, I like Functional Programming as much as anyone, but this all seemed like an implementation detail or stylistic choice to me. Testing side-effects is not that hard, right? If you don’t like mocking there’s also dependency injection, etc. Besides, even if you move side-effects to the infrastructure layer you still have to test that anyway! It all seemed to me like kicking the can down the road resulting in a less cohesive system to boot.

My main goal was to compress the concepts of Event Sourcing into a toy-like DX that felt familiar and frictionless to Ruby developers, so academic purity was not a big concern.

That niggling feeling that you’re missing something

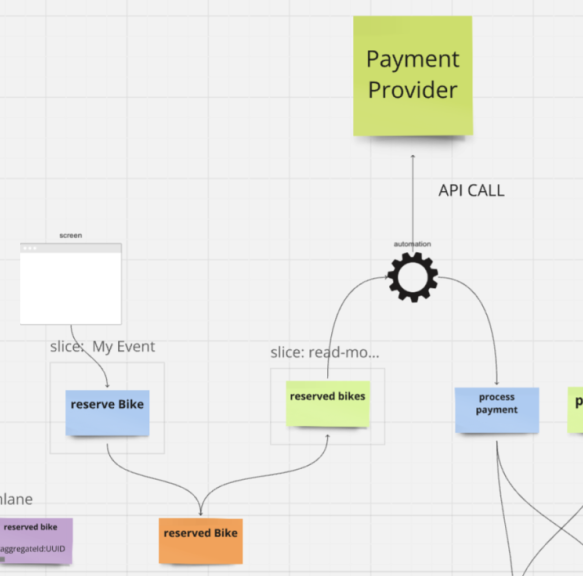

But I kept bumping into this issue. In particular, hanging out in the Event Modeling Discord, it was clear that the modeling conventions there dictated that all side-effects should happen in “Processors / automations”.

Now, I could totally see the utility of modeling things this way. Event Modeling is all about being explicit about the flow of information in a system at a high level, and this approach achieves that.

But it introduced tension in my mental model. If processors (the React step, when translated to my implementation) can also run side-effects, then surely they can also decide what command to run after those side-effects.

I hated this. Processors were smart! All of a sudden, my system’s capabilities were spread out onto two different layers. Command handlers and processors. This implied that React wasn’t just naively reacting in Decide’s footsteps, and Decide wasn’t the only decision-maker in town!

Commands really, really are about state changes

The other implication of this is what I’d dismissed as a mere detail before: command handlers really are pure, in that they only rely on past event history and their own properties to work. Given the same inputs, they lead to the same resulting events, every time. Commands don’t do the things in your app. They don’t send emails, or book flights.

It took this old comment in Stackexchange.com to finally make it click for me.

It’s not that pushing side-effects to the infrastructure layer is just a matter of convenience. It’s that an event-sourced domain is defined by the state changes it tracks, not the operations it performs. The entire domain is nothing but a big deterministic state machine definition (and command handlers are just the state guards?)

To be clear, it was always clear to me that events in Event Sourcing define state machines. But I always assumed that command handlers sat on top of that and mostly encapsulated entire capabilities including side-effects.

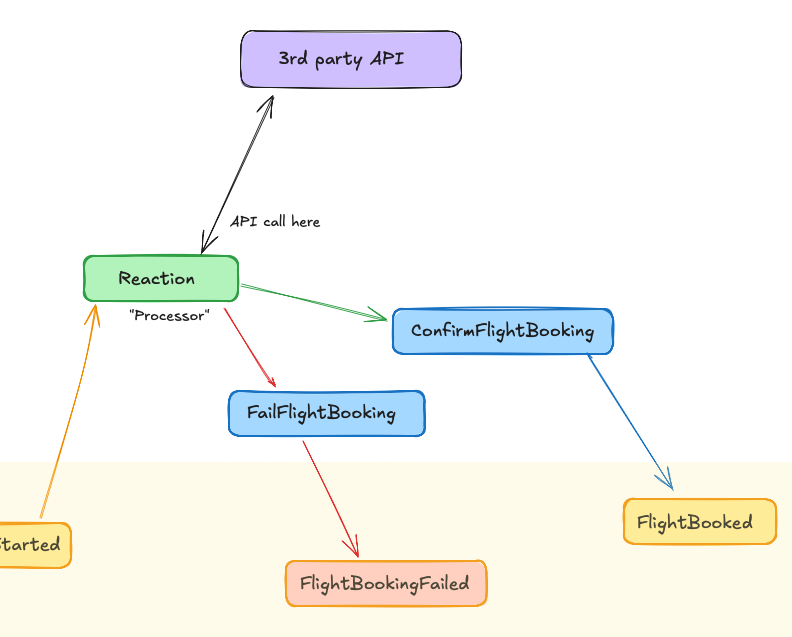

Smart links

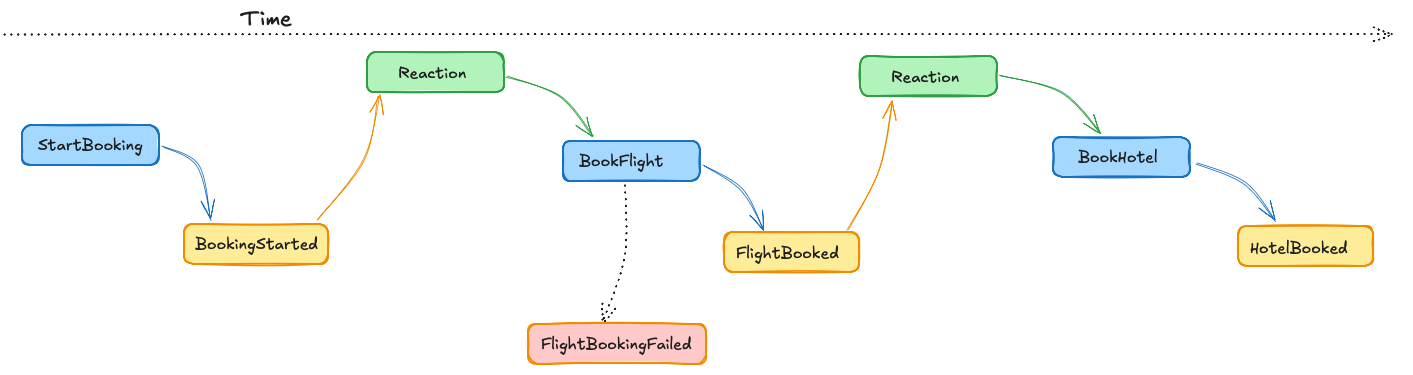

So, command handlers are somewhat downgraded to mostly guarding domain invariants. They carry with them all the state that they’re intending to update. Processors are upgraded into higher-level decision making. Given the current state of the system, I should gather any extra context I need to fulfill the next command in the workflow, including calling out to external systems, paging humans, etc.

Another way in which this is illustrated in Event Modeling is that processors (“React”) automate the work that normally a human would do. If you imagine a world where public APIs don’t exist, given a list of pending holiday bookings in the domain, a human would have to call the airline, hotel, etc. to make the bookings, then come back to the domain and manually dispatch commands with all the details to mark the bookings as completed. Again, I was aware of these analogies from early on, but they didn’t fully click until I downgraded my idea of the domain from doing things to tracking things.

Seen this way, I’m finding that the tension between Decide and React sort of melts away. Yes, they both make decisions, but they operate at different levels. Decide guards the state-tracking system. React evaluates that state, interacts with the world and decides what command to attempt next.

On naming these things

There’s still some tension between calling something “decide” when its decision-making remit is limited to guarding state transitions, and calling something else “react” when it actually decides what to do next. But I suspect this is just a mix up of technical and business concerns. “React” speaks to the fact that a component of the architecture is activated by new events. It’s a description of the mechanism, in other words. In other implementations you could have a process polling a view somewhere (a TODO list pattern). At a business level, you build Processors or automations on top of these mechanisms. I do feel now that “Processor” is also a bit too vague, though. “Bot” or “Automation” feels a bit more descriptive. If “agent” wasn’t already so tied to AI, I’d be tempted to use that instead.