This is part of a series on Event Sourcing concepts, with Ruby examples. Read the previous part: Event Sourcing with Ruby examples. The Event Store interface.

The Command Layer is conceptually the place where business logic happens, user input is handled and decisions are made.

It’s not by any means unique to event-sourced apps, but present in all kinds of software in one way or the other.

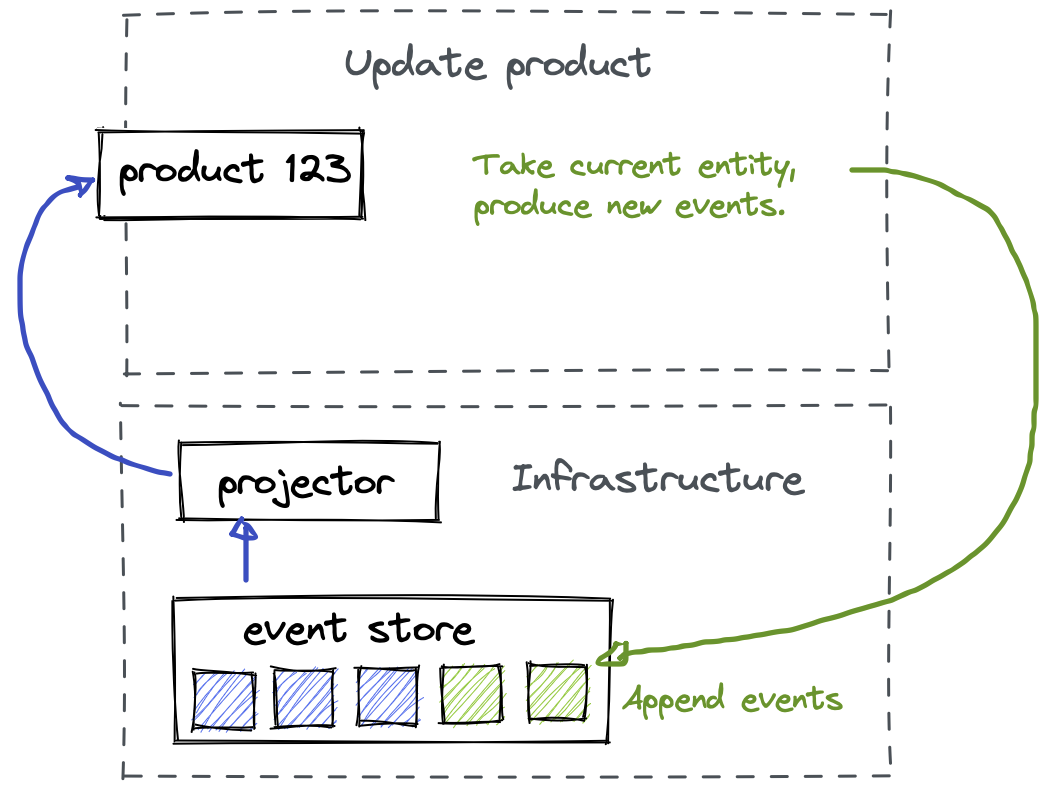

In event-sourced apps it can take many forms, but the general flow is this:

- Fetch an entity’s events currently stored in the Event Store.

- Reconstitute an entity’s current state by feeding an initial entity state and events in storage to the projector function.

- Inspect the current state, along with whatever input your command expects, run any validations needed, fetch any extra data needed to fulfill the command, and decide if any new events need to be issued.

- Produce new events, apply them to the entity via the projector function.

- Store the newly produced events back into the Event Store.

For example, a command function to update a product’s price.

BLANK_PRODUCT = { name: '', price: 0, brand: '' }

def update_product_price(product_id, new_price)

# 1. Fetch previous events from storage

events = EventStore.read_from_stream(product_id)

# 2. Reconstitute current product state from stored events

product = events.reduce(BLANK_PRODUCT, &ProductProjector)

# 3. Run any domain validations before issuing new events

raise ZeroPriceError, "product price must be above zero" unless new_price.positive?

# Rely on current state to check any domain invariants

if new_price < 1000 && product.brand == 'Apple'

raise ApplePriceTooLowError, "New price is suspiciously low for an Apple product"

end

# 4. If all is good, produce new events

new_events = [

PriceUpdated.new(new_price)

]

# Apply new events to product, so that you can keep validating current

# state, if needed

product = new_events.reduce(product, &ProductProjector)

# Any more validations and events here...

# 5. Store the new events back into the Event Store

EventStore.append_to_stream(product_id, new_events)

# Return the updated product along with new events produced

[product, new_events]

end

A pretty crude example but it shows the general workflow. In practice, your implementation of the command layer will vary depending on various criteria.

The point of entities

The example above already shows the main reason for an entity’s existence.

After all, entities themselves aren’t stored anywhere - other than as events in the Event Store -. They’re not used for listing, filtering, reporting, or anything else. An entity is sprung into life in your command’s memory just to let you interrogate the current state of your domain -to guard its invariants- and make decisions about what to do next.

In the example above we rely on the entity to find if the product at hand is by Apple, in which case we validate the minimum price.

This also guides the reasoning when designing entities in such a system. They should be whatever shape and data required to answer whatever questions are pertinent as a pre-requisite to changing state in your system.

For this reason, entitites in event-sourced systems tend to follow the Aggregate pattern, where a top-level “Aggregate root” acts as a gateway to changes in an entire graph of related objects. The root entity is the transactional unit.

Commands and CRUD

A “command” in your system could be just a controller action in a Rails application. In the example below I map a regular, CRUD-oriented update action into many granular events, depending on what attributes change.

# app/products_controller.rb

def update

product = reconstitute_product(params[:id])

new_events = []

if product_params[:price] != product[:price]

new_events << PriceUpdated.new(product_params[:price])

end

if product_params[:name] != product[:name]

new_events << NameUpdated.new(product_params[:name])

end

# Persist new events

EventStore.append_to_stream(params[:id], new_events)

# Redirect to #show action as per Rails conventions

redirect_to product_url(params[:id])

end

# The show action can also just reconstitute current product state

# from events in the Event Store

def show

@product = reconstitute_product(params[:product_id])

end

private

def product_params

params.require(:product).permit(:price, :brand, :name)

end

def reconstitute_product(product_id)

events = EventStore.read_from_stream(product_id)

events.reduce(BLANK_PRODUCT, &ProductProjector)

end

The example above is missing validations and error handling (the #show action should throw a 404 error if there’s no events for a product in the Event Store, ie. the product doesn’t exist).

Command objects

But a “command” can also be its own object, which is really an enhancement of the command-as-function in the first example. Still in Rails, commands can be implemented as ActiveModel objects.

# Inherit from some ActiveModel-based super class

class UpdateProduct < Command

attribute :product_id

attribute :price

attribute :name

attribyte :brand

validate :price, numericality: { min: 0 }

def run

return unless valid?

# this could be implemented in the Command super-class.

product = reconstitute_product(product_id)

product = apply_event(product, PriceUpdated.new(price)) if price != product[:price]

product = apply_event(product, NameUpdated.new(price)) if name != product[:name]

persist_events(new_events)

[product, new_events]

end

end

# Usage

cmd = UpdateProduct.new(id: params[:id], price: params[:price], ...etc)

cmd.valid?

cmd.errors

product, new_events = cmd.run

Note that there’s a lot of room for further abstractions here. Some frameworks encapsulate the process of fetching events from the Event Store and applying them to the Entity into its own layer, often hidden behind a repository interface.

Commands as messages

Yet another approach is to model commands as dumb value objects, similar to events, and have separate command handlers to process them.

UpdateProduct = Struct.new(:price, :name, :brand)

cmd = UpdateProduct.new(1000, nil, 'Samsung')

product, new_events = ProductCommandHandler.run(cmd)

This approach becomes useful when you plan to serialise commands and send them down a command bus or message broker, to be handled asynchronously by a separate process, background worker or micro-service.

A key difference with events here is that commands can -and should- validate their data.

cmd = UpdateProduct.new(1000, nil, 'Samsung')

raise "invalid command!" unless cmd.valid?

product, new_events = ProductCommandHandler.run(cmd)

Commands and side effects

Whatever your approach to the command layer, the important thing to note is that, because events are assumed to be immutable and deterministic, the command layer is the right place to check any pre-requisites and trigger any side-effects needed to issue new events. This could include fetching data from 3rd party APIs, sending emails, invalidating caches, etc.

In other words, while projecting a list of events over and over again should always arrive to the same result, commands don’t require such guarantees. The following is a command to calculate a product’s price in a different currency.

def change_product_currency(product_id, target_currency: 'GBP')

product = reconstitute_product(product_id)

# Call out to 3rd party API

new_price, rate = CurrencyExchangeAPI.call(

product[:price],

from: product[:currency],

to: target_currency

)

new_events = [

CurrencyChanged.new(product[:currency], target_currency, rate),

PriceUpdated.new(new_price)

]

persist_events(new_events)

end

Running this command at different times might return different values for the same initial money amount but, once committed to the Event Store, the resulting events are an accurate view of what changed, and the same current state can be derived from them over and over again.

What’s more, you get a full audit trail of any changes in the state of the world at the point in time when the command was run.

# 2022-06-01T10:11:00 [product-123] currency changed from USD to GBP at 0.82

# 2022-06-01T10:11:00 [product-123] price updated to GBP 820.00

Commands are actions to run now. Events are the historical trail left behind by those actions.

Things to note:

- Projecting events gets you the same results every time. Running commands does not, necessarily.

- While events represent “facts” that happened in your domain, commands represent “intents”, and as such are not guaranteed to succeed or lead to any events being produced.

- Because they are intents, commands should be thought of as the closest component to the end user in terms of their semantics and naming. Ex. in web apps they often map directly to HTML forms, and map well to task-based UIs.

Committing commands to history

Previously I mentioned that one approach to the command layer takes the form of event-like value objects.

ChangeProductCurrency = Struct.new(:user, :product_id, :target_currency)

This suggests that commands could, too, be serialised and committed to the Event Store.

EventStore.append_to_stream("product-123", [

change_product_currency,

currency_changed,

price_updated

])

But wait. Why would we do this? Doesn’t this blur the whole command/events distinction I’ve been making all along?

It’s true, projecting a command into entity state doesn’t make sense -commands are the things that produce state changes, not the state changes themselves-. Entity projectors can safely ignore them. But there’s still value in committing them to history even if we don’t use them in projections.

For one, we can give unique IDs to commands and events, and annotate events with the IDs of the commands that produced them.

# Commands

ChangeProductCurrency = Struct.new(:id, :user_id, :product_id, :target_currency)

# Events

CurrencyChanged = Struct.new(:id, :command_id, :source_currency, :target_currency, :rate)

PriceUpdated = Struct.new(:id, :command_id, :price)

All things set up correctly, we gain a full audit trail of both user intents and the resulting events.

# 2022-06-01T10:11:00 [product-123] user xyz attempts to change currency to GBP

# -- 2022-06-01T10:11:00 [product-123] currency changed from USD to GBP at 0.82

# -- 2022-06-01T10:11:00 [product-123] price updated to GBP 820.00

This helps paint a fuller picture of the system’s behaviour.

In this model, commands and events are both treated as messages in storage, but at the application level they retain their distinct semantics and are handled by different layers.

Another advantage of this, especially for multi-service systems, is that other services can pull commands from the Event Store and handle them on their side, possibly resulting in new events, and even new commands, committed to the store. This approach effectively uses the Event Store as an asynchronous command bus or message broker for inter-system collaboration. You can read about CQRS and Sagas for more.

Pushing the infrastructure to the margins

Most of the code examples in this article handle fetching and committing events to the store explicitely as part of the command code. This can be unavoidable, and even desirable, in command code for CRUD apps, or anywhere where domain objects must interact in heterogeneous ways with one or more persistence layers.

But Event Sourcing gives us a clear boundary between domain logic and persistence, in the form of a simple dataflow and a uniform two-method interface in the Event Store. All commands interact with the persistence layer in the exact same way: they fetch events for an entity, and then append new events for the same entity.

This means that we can separate concerns within the command layer into domain logic for each use case, on one hand, and the generalised persistence infrastructure on the other.

The implementation of this can take many forms, but its value becomes apparent if we think of how these simpler commands could be tested.

describe UpdateProductCommand do

specify 'given a product and a new price, it returns the right events' do

product = { price: 1000 }

events = UpdateProductCommand.call(product, price: 2000)

expect(events).to eq([

PriceUpdated.new(2000)

])

end

end

Given current state and user inputs, we expect one or more events in return. We test the domain layer by asserting its behaviour in the form of events produced. The details of persistence can be pushed out of the way, into a generic infrastructure layer.

What’s really nice about this is that we’re effectively “flattening” the entire behaviour of a system into a well defined specification, a protocol of sorts that exists at a single layer of abstraction: a list of commands and their corresponding events.

This approach potentially opens the door to composable command pipelines, where a broad, CRUD-oriented command such as

UpdateUsercan be composed of more fine-grained steps in a chain (UpdateEmail,UpdateName, etc). Using Railway-style pipelines can be a good model to glue those steps and handling error cases.

In the wild: command and entity mashups

Some libraries and frameworks out there merge entities and command handling, such that commands are just method calls in the entities themselves.

product = Product.new

product.update_price(1000) # this produces and applies a PriceUpdated event, internally

product.price # 1000. Event has been applied internally.

product.new_events # New, uncommitted events [PriceUpdated]

Some even go further and mix the Event Store itself into entities, to provide ORM-like functionality.

product.save # persists entity uncommitted events into Event Store

I think this is a design mistake. Commands are really policy objects that could vary depending on context. For example, an Admin user might be able to update a product’s price, whereas a regular user might not. So you could have separate command handlers tied to user permissions even if they rely on the same entity for state.

Also as said before, this pollutes entity code with loads of unrelated implementation detail (side effects, validations, API calls) and your entities will unavoidably grow bloated as the project progresses. Entities should be in-memory representations of objects in your domain, enough to answer questions such as “what is the current price of this iPhone?” or “does this user have write permissions?”, and nothing else. How those objects come to be, and how and under what circumstances they change, should be handled by distinct layers in the system.